Overview

The Sirens were creatures from Greek mythology famously known for their enchanting and deadly music, which, according to legend, no sailor could ever resist.

Their origins are a bit of a mystery, with various stories pointing to different divine parents. Some say they are the daughters of the sea god Phorcys or that the river god Achelous coupled with one of the Muses—goddesses known for their influence over the arts and sciences. This family tree of gods and muses might suggest why the Sirens are so closely linked to the dangerous allure of the sea and the captivating power of music and poetry.

In many of these tales, the Sirens are found on a remote island, lying in wait for unsuspecting ships to pass by. The island itself is as lethal as the Sirens, covered in the bones of sailors who’ve fallen victim to their songs. More than just a backdrop, the island is thought to symbolise the dangerous pull of desires that, if given in to, can lead to ruin.

The number of Sirens mentioned varies with each storyteller. Homer, in his epic “Odyssey,” doesn’t specify a number, while other ancient authors like Hesiod identify three named Sirens.

Want to know more? Read on…

Watch the related video

Etymology

The term Siren in Greek mythology brings to mind danger and enchantment, reflecting its deep linguistic roots. The word “Siren” (Greek Σειρήν, transliteration Seirḗn; plural “Sirens,” Greek Σειρῆνες, transliteration Seirênes) dates back to the Mycenaean period (around 1600–1050 BCE), where it first appeared in the Linear B script as se-re-mo. This script was used before the Greek alphabet was developed.

Etymologically, “Siren” is often connected to the Greek word σειρά (seirá), which means “rope.” This link suggests the idea of binding or entangling, much like the Sirens’ mythological role in captivating sailors with their enchanting music and leading them to their doom.

Scholars have proposed various interpretations of the term that add depth to our understanding of these mythical creatures. Others have thought the Sirens might be linked to Sirius (Σείριος, Seírios), the bright star associated with heat, possibly pointing to the intensity of the Sirens’ allure. Wilhelm Brandenstein proposed that the term might be a Thracian loanword related to the Indo-European root *ĝʰer, meaning “to delight in.” Others, such as Pierre Chantraine and Robert Beekes, believe that the name is of pre-Greek origin, indicating that it may not be an Indo-European word at all.

In the 19th century, some academics suggested that “Siren” could stem from Semitic roots, with terms like šyr, meaning “song.” This could lead to combinations like šyr ḥn, “song of grace”; šyr ’n, which could mean “song of entrapment” or “song of mourning”; or šyr ’ymh, “song of terror.” Another theory is that it comes from the Ugaritic term šyrm, meaning “singers.”

Pronunciation

The correct pronunciation of “Siren” in modern English is typically \ˈsī-rən\, with a clear emphasis on the first syllable. For those interested in the classical Greek pronunciation, it approaches \sei-‘rēn\, where the ‘ei’ is pronounced as a long ‘i’ sound, much like in the English word ‘sight’.

Pronunciation

ENGLISH

Siren

GREEK

Σειρήν

PHONETIC

[SAHY-ruhn]

IPA

/ˈsaɪ rən/

Alternate Names

Throughout Greek literature, Sirens have also been referred to by various names and titles that echo their mythological functions. Some of the alternate names include:

- Σειρῆνας (Seirēnas): This is simply the plural form in Greek, often used in ancient texts.

- Enchantresses of the Sea: A poetic title that encapsulates their role and the domain over which they preside.

Individual Names of Sirens

The earliest writings about the Sirens in Greek mythology didn’t provide specific names for these enchanting creatures. While Homer’s “Odyssey” wrote about them, it didn’t mention how many or their names, and other ancient texts vary in their accounts.

Number and Names of Sirens Across Different Sources:

- Homer did not specify a number, often interpreted as two Sirens based on later artistic depictions.

- Hesiod, another early source, does not offer names or a definite number either.

- Plato spoke of more conceptual Sirens in his works, and his mention of eight is symbolic in the context of his philosophical discussions rather than a literal count.

As mythology evolved, later writers and poets began to name and number the Sirens more distinctly, often listing three as the most commonly accepted number:

- The trio of Parthenope, Leucosia, and Ligia is one of the most frequently cited groups in later myths and artistic depictions.

- Another set includes Pisinoe, Aglaope, and Thelxiepia, offering a slightly different take on the individual characteristics and stories of the Sirens.

- Additional variations exist, such as Aglaonoe, Aglaopheme, and Thelxiepia; or Thelxiope (or Thelxione), Molpe, and Aglaophonos; some accounts also name trios like Teles, Molpe, and Thelxiope.

Some later traditions revert to the idea of just two Sirens, named Aglaopheme and Thelxiepia, aligning more closely with the earlier depictions of Homer’s story. Interestingly, a rare depiction on an early fifth-century BCE stamnos (a type of ancient Greek jar used for liquids) introduces a Siren named Himeropa. This name is unique and not widely recognised in other ancient texts, indicating the variety and regional differences in Siren myths over time.

Attributes

Appearance

In the earliest Greek depictions, Sirens were imagined as creatures with the bodies of birds and the heads of women. But interestingly, our first written source comes from Homer’s Odyssey, written around the eighth century BCE. In this epic, there is no physical description of the sirens. Our view of what they looked like came from historical artefacts such as perfume bottles, vases, funerary pots and mirror decorations. It was around the 6th century BCE that the art of the sirens showed them as part birds, part human creatures, with wings and always depicted near to the sea.

Though it might be easy to make the connection to the birds for their singing, it might not be easy to see their association with death and water. One theory is that there is a connection with a mythological creature found thousands of years earlier: the Egyptian Ba-Bird.

The ancient Egyptians thought each person was made up of several parts. A key part was the “Ba,” considered the person’s spirit. After death, this spirit was pictured as part bird and part human, showing it could fly away from the tomb but had to return.

Egyptians also believed that another part of the soul needed to cross a lake to get to eternal life after being judged. The Ba looked like the person it came from, which means it could be male or female. This helps explain why some Sirens in Greek stories are male, even though most are female.

The idea of the Ba has been around for a long time, showing up in Egyptian art from around the 15th century BCE. That’s hundreds of years before Homer might have written his stories.

By the 6th century BCE, Greeks were visiting Egypt often because trade across the Mediterranean had gotten easier. This meant not just goods, but also ideas were shared between the two cultures. That’s why some people think that the Egyptian Ba-bird could have inspired the Greek idea of Sirens, especially since both are linked to death and have similar looks.

This iconography frequently appeared in funerary art, suggesting a connection with themes of death and the afterlife, possibly as messengers or guardians between worlds. In classical times, Sirens were often depicted holding musical instruments such as lyres or flutes, reinforcing their mastery over music and its profound effects.

Their regular appearance on sarcophagi and in scenes with underworld deities like Hades and Persephone highlights the belief in their music’s connection not only to physical seduction but also to spiritual transition and transformation.

Becoming Mermaids

There is continued debate about whether sirens are the same as mermaids and vice versa. While the original versions were clearly not fish-tailed creatures, later art and stories began to transform sirens into these underwater creatures.

Art from as early as the 7th century CE shows the first siren in the form of a fish-woman. In this period, the “Book of Monsters” also mentions sirens, describing them with a woman’s upper body and a scaly tail.

By the early 13th century, more images and texts depict sirens with fishtails. For example, “Otia Imperialia,” an encyclopedic work, mentions sirens living off the coast of Britain. It describes these creatures as having a female head, shiny long hair, and a woman’s torso up to the navel, while the rest of their body resembles a fish.

Their enchanting songs were said to captivate sailors’ hearts so deeply that they would often forget their duties and encounter shipwrecks due to their carelessness.

While their appearance evolved, their nature remained unchanged: sirens were always seen as perilous. By the 14th century, “The Book of Ballymote,” an old Irish text, explicitly links these enticing women to death. In this tale, sailors meet nine beautiful sirens on a submerged island.

The sirens detain the ship for nine days and reward the men with gold under the condition that they return seven years later. As the sailors pass by the island again, they attempt to steer clear of the sirens. Despite their efforts, the sea women chase them, singing a mournful song. In a grim turn of events, one siren kills a child she had with one of the sailors and throws the body at the devastated father.

While mermaids have their distinct stories, it’s crucial to recognise that the tale of the seductive siren and her dangerous song is part of that legend, yet distinctly its own narrative.

Their Abilities

At the heart of the Sirens’ mythological identity is their hauntingly beautiful song, renowned across various myths for its supernatural allure and deadly impact. This song is capable of drawing sailors towards perilous waters or desolate shores, ultimately leading to their doom.

When Odysseus decided to leave Aeaea and return to Ithaca, the heartbroken Circe gave him a warning of the sirens that he would meet on his journey home:

“First you will come to the Sirens, who enchant all who come near them. If anyone unwarily draws in too close and hears the singing of the Sirens, his wife and children will never welcome him home again, for they sit in a green field and warble him to death with the sweetness of their song.”

Homer, The Odyssey (Book XII)

Representing the ultimate temptation, the Sirens’ song symbolises the dangerous lure of giving in to destructive desires. More than just a bewitching melody, their song is meant to serve as a metaphor for the challenges, temptations, and transformations heroes must endure.

Island of the Sirens

In ‘The Odyssey,’ Homer places the Sirens somewhere to the west, near the daunting straits of Scylla and Charybdis, with other tales suggesting they resided on the flower-rich island of Anthemoessa. It’s commonly believed that the Sirens, like other mythical beings encountered by Odysseus, were located off the coasts of Italy or Sicily. Homer vividly describes the Sirens’ environment:

“…as they sit in a meadow, and about them is a great heap of bones of mouldering men, and round the bones the skin is shrivelling.”

Many think the Sirens lived off the coast of Campania, close to landmarks like Cape Pelorum, the island of Capri, Surrentum (today’s Sorrento), or the Sirenoussae Islands—each known for their ship-wrecking rocks.

The Sirens are also connected to various sites in mainland central and southern Italy, where it’s said their remains washed ashore. Notably, Siren Parthenope is associated with Naples, Leucosia with her namesake island, now Licosa, and Ligia with Terina in modern-day Calabria.

There’s a lesser-known story that the Sirens might have lived in the Far East, possibly India, or near Crete, in the area known as the White Islands (Leucae).

Family

The most commonly accepted origins of the Sirens place them as daughters of the river god Achelous and one of the Muses. Depending on the myth, this could be Melpomene (Muse of Tragedy), Terpsichore (Muse of Dance), or Calliope (the Muse of epic). Achelous’s father was the Titan Phorcys, Sea god, often associated with the hidden dangers of the sea.

The Muses, goddesses of the arts, endow the Sirens with their mesmerising voices and musical talents, which are central to their identity and mythological role.

Family Tree

Grandparents

Grandfather

Phorcys

Parents

Father

Achelous

Mother

Melpomene, Terpsichore, Calliope

Mythology

Homer’s Odyssey

In Homer’s “Odyssey,” the tale of Odysseus and the Sirens unfolds during his long journey back to Ithaca after the Trojan War. Guided by advice from Circe, an enchantress and a minor goddess, who knows the perils of the seas, Odysseus is warned of the enchanting yet deadly song of the Sirens. These mythical creatures inhabit an island that Odysseus must navigate past.

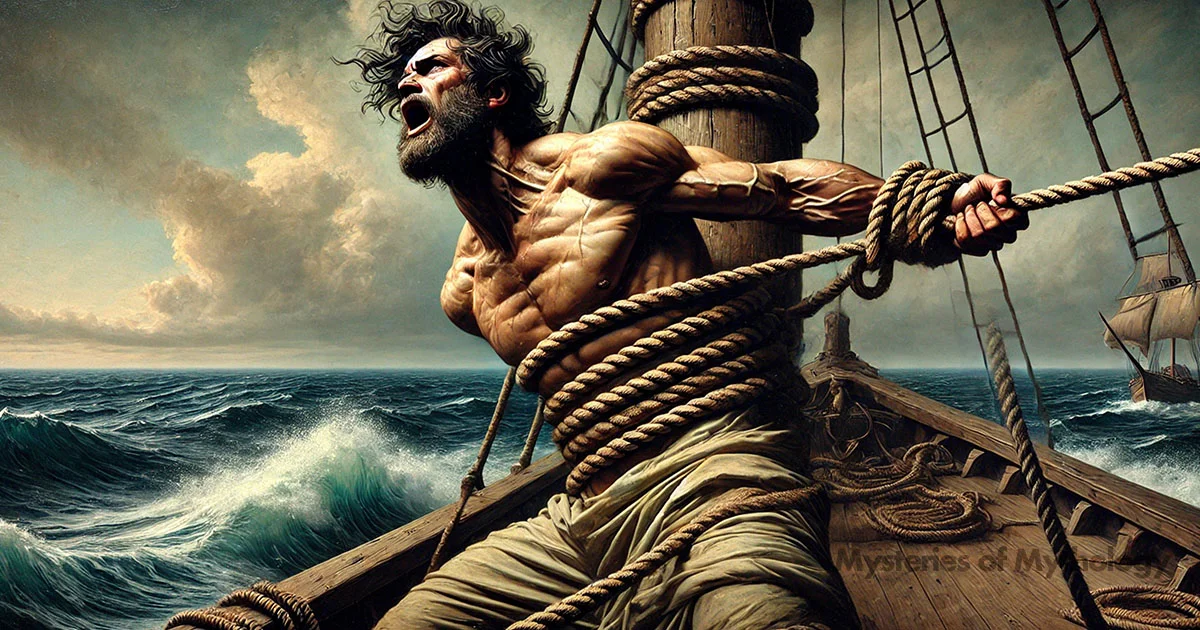

To safeguard himself and his crew, Odysseus devises a plan. He orders his sailors to fill their ears with beeswax, blocking out the seductive calls of the Sirens. Driven by curiosity, Odysseus instructs his men to tie him tightly to the ship’s mast. He commands them not to release him under any circumstances, no matter how much he might beg or plead once he hears the Sirens’ song.

As their ship approaches the Sirens’ island, the air fills with the hauntingly beautiful melody of the Sirens, aimed directly at Odysseus. True to his predictions, he finds their song irresistible and, overcome by his desire to hear more, begs his crew to set him free. But his loyal crew, unable to hear the song and committed to their captain’s earlier orders, binds him even tighter and continues rowing until they have safely passed beyond the reach of the Sirens’ voices.

“Come hither, as thou farest, renowned Odysseus, great glory of the Achaeans; stay thy ship that thou mayest listen to the voice of us two. For never yet has any man rowed past this isle in his black ship until he has heard the sweet voice from our lips. Nay, he has joy of it, and goes his way a wiser man. For we know all the toils that in wide Troy the Argives and Trojans endured through the will of the gods, and we know all things that come to pass upon the fruitful earth.”

Some have said that Odysseus was enticed not by their singing but by the knowledge that the sirens had of all things.

Argonautica

In the “Argonautica,” an epic poem chronicling the voyage of Jason and the Argonauts, the Sirens pose a similar mystical threat as in Homer’s “Odyssey.” The Argonauts, like Odysseus, must pass by the Sirens, whose enchanting songs have the power to lure any sailor to his doom. Aware of the danger, the crew prepares to navigate these treacherous waters.

The hero of this tale, Jason, is accompanied by Orpheus, who is famed for his divine musical abilities. As the ship approaches the Sirens’ realm, the danger becomes imminent. The Sirens begin their haunting song, aiming to captivate the Argonauts as they had many before. But Orpheus, understanding the peril, takes up his lyre and plays a melody so beautiful and powerful that it overshadows the Sirens’ song.

Orpheus’ music not only drowns out the deadly lures of the Sirens but also fortifies the resolve of the crew, allowing them to pass safely without succumbing to the temptation.

Transformation and Curses

According to Ovid’s “Metamorphoses,” the Sirens were originally companions to Persephone, the daughter of Demeter. Following her abduction by Hades, Demeter was overwhelmed by her daughter’s disappearance. In her despair, she transformed the Sirens into creatures with the bodies of birds and the heads of women.

This transformation served two roles: it was both a punishment for their failure to prevent Persephone’s kidnapping, and so they could better help Demeter in the search for her daughter.

In another version of their story, the Sirens were originally young women who decided to live their lives as virgins. This decision upset Aphrodite, the goddess of love, who didn’t take kindly to their choice to avoid love and romance. In response, Aphrodite transformed them into part-bird creatures with the power to sing irresistibly beautiful songs. These songs had a deadly side effect: they lured sailors to their doom.

Seeing the danger they posed, Zeus, the chief of the gods, stepped in and gave the Sirens a new home on the island of Anthemoessa. This island, surrounded by treacherous waters, became their haunting ground, where their enchanting music led many sailors to shipwreck. This place perfectly matched the Sirens’ sad but dangerous nature, turning into a legendary spot marked by numerous maritime tragedies.

The Death of the Sirens

Different myths tell us about the tragic endings of the Sirens, and these stories mainly started appearing much later in Greek history, around the Hellenistic period (323–31 BCE).

One popular story tells us that the Sirens would only live until someone managed to hear their song without falling into their trap. This prophecy came true thanks to Odysseus being tied to the ship’s mast (see above). After they safely passed the Sirens, the defeated creatures threw themselves into the sea out of despair. It’s said that their bodies later washed up on the shores of Italy, sparking various local legends about where they ended up.

In another tale, the Sirens’ story ends—or they go through a big change—after they lose a singing competition to the Muses. The Sirens dared to challenge the Muses but lost the contest. After their defeat, the Muses took the Sirens’ feathers to make crowns for themselves as a trophy. Left featherless and ashamed, the Sirens jumped into the sea and turned into the Leucae Islands, near the Cretan town of Aptera, which means “Featherless.”

Pop Culture & Modern Representations

The myth of the Sirens has evolved, but remained popular, appearing in various modern representations that captivate audiences worldwide. Here are some specific examples of how Sirens have been adapted in contemporary media:

- Movies: In Pirates of the Caribbean: On Stranger Tides (2011), the Sirens appear as mermaid-like creatures who use their beauty and song to lure sailors into deadly traps, aligning closely with their mythological roots.

- Television: The TV series Siren (2018-2020) reimagines Sirens in the modern world, focusing on a mysterious girl who arrives in a coastal town and unleashes a battle between man and sea creatures. The show explores themes of ecological protection and the deadly nature of Sirens.

- Literature: In To Kill a Kingdom by Alexandra Christo, Sirens are depicted as lethal beings who harvest the hearts of princes, adding a dark twist to their allure and the fatal consequences of their enchantment.

- Music: The band Florence and the Machine’s song “Ship to Wreck” (2015) metaphorically uses the concept of Sirens to describe self-destructive behaviours, echoing the mythological theme of irresistible yet dangerous calls leading to one’s downfall.

The Siren Instrument

The Siren, a device capable of producing a loud, piercing sound, was invented in 1872 by the Scottish physicist John Robinson. Originally designed for acoustic experiments, the mechanical Siren quickly found its way into various safety and warning systems.

Over time, this instrument has become synonymous with alert systems used by emergency vehicles and civil defence sirens. It serves as a modern-day herald of critical situations, mirroring the urgency and impact of the Sirens’ call in mythology.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is a Siren?

A siren is a mythical creature from Greek mythology known for its captivating and deadly song. Traditionally depicted as beings with the head of a woman and the body of a bird, sirens lured sailors to their deaths with their enchanting music.

Are Sirens and Mermaids the same?

No, sirens and mermaids are not the same. While both are mythical creatures associated with the sea and known for their alluring nature, traditional sirens are part-bird, part-woman creatures who sing to attract and destroy sailors. Mermaids, on the other hand, are typically depicted as having a human upper body and a fish tail, and they appear in various folklore across the world, not just Greek mythology.

What is the story of the Sirens?

In Greek mythology, the story of the sirens often involves them using their mesmerizing songs to lure sailors to their island, where the sailors meet their demise. The most famous story involving the sirens is found in Homer’s “Odyssey,” where Odysseus cleverly avoids their fate by having his crew plug their ears and tying himself to the mast of his ship to safely listen to their song.

Why did Sirens get cursed?

According to some versions of their myth, the sirens were cursed by the goddess Demeter as punishment for not preventing the abduction of Persephone, her daughter. Demeter transformed them into bird-like creatures with women’s heads, destined to live only until someone heard their song and passed by unharmed.

Why do Sirens kill sailors?

In mythology, sirens kill sailors not out of malice but as a consequence of their nature. Their irresistibly beautiful song compels sailors to steer their ships towards the dangerous rocks of the sirens’ island, leading to shipwrecks. This lethal outcome illustrates the perilous allure of their music, symbolizing the dangers of temptation.

References

- Austern, Linda. Music of the Sirens. Indiana University Press, 2006.

- “Ba-bird.” The Met Museum. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/.

- Bestiary, fol. 10r. c. late 12th century.

- Bestiary, with extracts from Giraldus Cambrensis on Irish birds. England, S. (Salisbury?), c. 13th century.

- Cooney, John D. “Siren and Ba, Birds of a Feather.” The Bulletin of the Cleveland Museum of Art, vol. 55, no. 8, Oct. 1968, pp. 262–271.

- Evans, Elaine A. “Ancient Egyptian Ba-Bird.” McClung Museum of Natural History and Culture. https://mcclungmuseum.utk.edu/1993/11/.

- Fitzgerald, David. “The Myth of the Sirens.” The Academy, issue 487, Sept. 3, 1881, p. 182.

- G., P. A Most Strange and True Report of a Monsterous Fish, Who Appeared in the Forme of a Woman, from Her Waste Vpwards. London, for W.B, 1604.

- Gray, Douglas. Simple Forms: Essays on Medieval English Popular Literature. Oxford University Press.

- Harrison, Jane E. “The Myth of Odysseus and the Sirens.” The Magazine of Art, 1887, pp. 133–136.

- Homer. The Odyssey, Book 12. Translated by A.T. Murray, Classical Library, vol. 1, Harvard University Press, 1924. https://www.theoi.com/Text/HomerOdyss/.

- Kaplan, Matt. The Science of Monsters. Scribner, 2013.

- Muhlestein, Kerry, and John Gee. Evolving Egypt: Innovation, Appropriation, and Reinterpretation In Ancient Egypt. E-book, Oxford, UK: BAR Publishing, 2012. https://doi-org.ezproxy1.lib.asu.edu/.

- Northumberland Bestiary. c. 1250-1260. http://www.getty.edu/art/collection/.

- Ovid. Metamorphoses. Translated by Rolfe Humphries, 1983. (Ovid’s work tells one version of the Sirens’ origins.)

- Peraldus. Theological Miscellany, Including the Summa de Vitis. England, c. 13th century after c. 1236. https://www.bl.uk/catalogues/illuminatedmanuscripts/.

- Psalter. England, between 1310-1320. https://www.bl.uk/catalogues/illuminatedmanuscripts/.

- Rhodius, Apollonius. The Argonautica. Translated by R.C. Seaton. Project Gutenberg, 1912. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/830/830-h/830-h.htm.

- Romano, Stefania, et al. “Beyond the Myth: The Mermaid Syndrome from Homerus to Andersen: A Tribute to Hans Christian Andersen’s Bicentennial of Birth.” European Journal of Radiology, vol. 58, 2006, pp. 252–259.

- Tandjung, Beverly. “The Enchantress of the Medieval Bestiary.” The Iris, May 11, 2018. https://blogs.getty.edu/iris/the-enchantress-of-the-medieval-bestiary/.

- The Etymologies of Isidore of Seville. Edited by Stephen A. Barney et al., Cambridge University Press, 2006.

- Zabkar, Louis V. “Herodotus and the Egyptian Idea of Immortality.” Journal of Near Eastern Studies, vol. 22, no. 1, Jan. 1963, pp. 57–63.